UPDATE: This article received the 2024 President’s Writing Award from the American Institute of Parliamentarians.

Large annual meetings and conventions create special demands on the parliamentarian. For example, numerous business items may move very quickly with lightning speed. The large audience and attendees milling about make it difficult to see who wishes to be recognized to speak. Votes by voice or even standing can be hard to judge, and the organization may not have electronic voting capabilities. Larger crowds gathered in one place create problems that are not present in smaller board or membership meetings. (See Board Procedures Versus a Membership Meeting or Convention)

That said, Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised and other parliamentary manuals tend to focus more on meeting procedure than these kinds of practical concerns. Having started 30 years ago, I’ve served as parliamentarian to several hundred meetings with between 500 and 8,000 participants. Here are some pro tips for better assisting large meetings. Being aware of these techniques will make you a better parliamentarian, regardless of what types of meetings you attend.

FACILITATING RECOGNITION

In a small body, recognition of members wishing to speak is usually not difficult. After all, there may only be one or two members attempting to claim the floor. But in huge meetings with numerous members seeking recognition, it can be difficult for the chair to know whom to call on first, particularly given the numerous recognition rules that should be followed. For instance, members who have not yet spoken on a specific motion have preference over those who have spoken. The chair is supposed to alternate the floor as far as possible between those favoring and those opposing the measure. (See RONR (12th ed.) 3:33) The chair can facilitate this process by asking, “Is there anyone who would like to speak who has not yet spoken?” or “Is there someone who would like to speak for [or “against”] the motion?”

Even these methods don’t work well at large in-person conventions with numerous microphones (one meeting I attend each year has 36!). Of even greater concern is that some motions are waived if not raised immediately (Point of Order, Division, Objection to Consideration). Without a process for recognizing such delegates immediately, an entire convention can become derailed. Robert’s recognizes that in “large conventions or similar bodies, some of the rules applicable to the assignment of the floor may require adaptation.” (RONR (12th ed.) 42:16) Most often, this is accomplished by a card, telephonic, or electronic recognition system described within standing or special rules.

While there are various card-recognition systems, a low-tech method is to have several cardstock colored cards, such as green, red, yellow, and white at each microphone. To speak in favor of a motion, a delegate raises a green card and awaits recognition. To speak against a motion, a delegate raises a red card and awaits recognition. The chair utilizes the green and red cards to alternate between pro and con speakers. Subsidiary motions, such as to Postpone Indefinitely, Refer, or Postpone, can be made on either a green or red card. The yellow card allows a member to “jump ahead” of delegates with green or red cards for certain motions, such as for a Request for Information or to Suspend the Rules. A white card immediately interrupts all business and is used for urgent matters, such as a Point of Order, Appeal, or Objection to Consideration. Spotters on stage can help the chair and parliamentarian keep track of speakers by arranging colored notecards in the correct order and handing them to the parliamentarian for review. Particularly for large conventions, the card-recognition system is an inexpensive means of alternating debate and recognizing certain motions ahead of other motions. (See also How to Avoid Yellow Card Hell)

Similar but more technologically sophisticated recognition methods include telephonic and computer-based systems. With either, delegates call-in or log-in a desire to speak along with the wording of any planned motions. These are organized in terms of when the motion is received as well as the precedence of the motion and given to the parliamentarian for review.

VOTING CARDS

Although COVID-19 concerns have (thank goodness) subsided, not everything about large meetings has gone back to how it used to be done. For instance, the most common method pre-pandemic of voting during large meetings was by voice. On any matter to be decided, the presiding officer would ask all those in favor to say “AYE,” and those opposed to say “NO.” Even following the virus, both leaders and health professionals have questioned whether hundreds or thousands of delegates should all be yelling in a crowded room at the same time, masked or not.

There are alternatives to voting by voice. Some organizations with the capability and resources have gone electronic. Such platforms can vary from voting by electronic handheld devices provided to members to cell phone apps to an online voting site accessed through electronic device during the meeting. Depending on method and size of the organization, there can be costs and often a learning curve. While voting electronically can give an exact count (and is extremely valuable when delegates carry different numbers of votes or some members are participating remotely), it also alters the dynamics of the room to more passive participation. Voting electronically during conventions is similar to using a remote control for a television–it is quiet and feels different from active member participation voice or standing vote.

Voting cards are a low-budget alternative to voice votes in large meetings. The technique is described only briefly in Robert’s as a “brightly colored cardboard card, approximately three inches wide and a foot long” traditionally used in some political conventions. (RONR (12th ed.) 45:16) A more common meetings practice is for delegates to be given a larger sheet, most often cardstock measuring 8½” by 11″. Then, when the presiding officer calls for a vote, the language is to the effect of “Those in favor of Bylaws Amendment #3, raise your card. . . Those opposed, raise your card.” (Some organizations use two cards, with “AYE” printed on a green card and “NO” on the red.) Whatever the specifics, “If this method of voting is to be used, it must be authorized by a special rule of order or, in a convention, by a convention standing rule.” (RONR (12th ed.) 45:16)

Voting cards have several benefits. Seeing the vote makes it easier to determine whether a matter has passed or failed than a voice vote alone, even when a vote requires a two-thirds or other percentage vote. (I once had a President tell me she “loved” seeing the sea of green cards.) Since the members see the vote in real-time, there will be less need for members to challenge the vote through a Division after a voice vote. Finally, voting cards can be cheaper and less confusing than electronic voting and feel more participatory than electronic devices. (See also Voting Cards at Conventions & Annual Meetings)

COMMUNICATING WITH THE CHAIR

“It is also the duty of the parliamentarian—as inconspicuously as possible—to call the attention of the chair to any error in the proceedings that may affect the substantive rights of any member or may otherwise do harm” (RONR (12th ed.) 47:50). However, “in advising the chair, the parliamentarian should not wait until asked for advice—that may be too late” (RONR (12th ed.) 47:51). As a result, some parliamentarians utilize methods for communicating—as inconspicuously as possible—throughout the business portion of a convention. Parliamentarians have several techniques for doing this, particularly when it comes to large, complex meetings.

Some parliamentarians use a type of card system to communicate during the meeting with the presiding officer. (See Notes and Comments on Robert’s Rules, Fifth Edition, p. 188-189) Such cards can be note-sized or larger and have a brief description of the wording to process different motions. While the cards can be handed to the presiding officer, they are often clipped or attached to the lectern so that all cards for pending motions are visible to the presiding officer. The chair, by glancing at the lectern, can see the order of all pending motions as well as the specific wording for each. For instance, the card for taking the vote on the motion to Amend might read as follows:

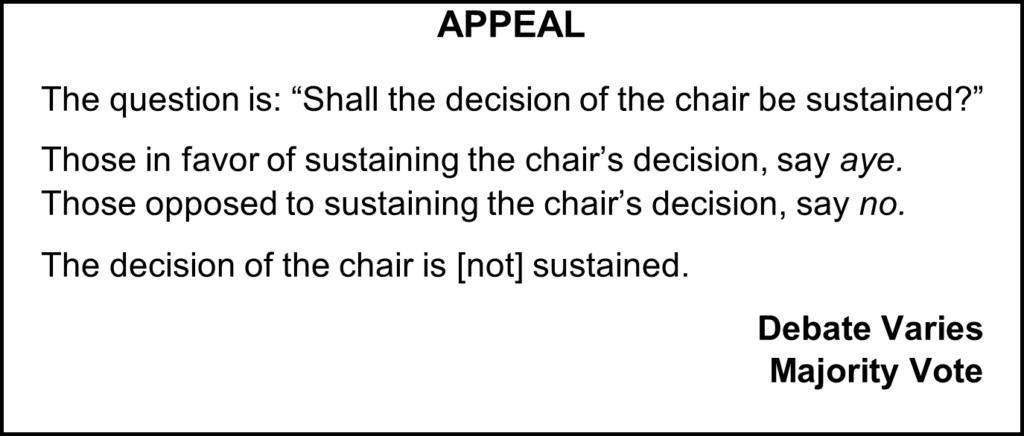

The card for handling an Appeal might read:

The card system is professional, flexible, and inconspicuous. While the presiding officer is conducting the meeting, it is with the assistance of the parliamentarian. The chair should be familiar with the cards before the convention begins. Otherwise, the cards will appear foreign rather than an aid. The key for the chair: Trust the cards.

The precise wording on any card will vary based on the parliamentary authority, the specific motion, and the organization’s past practice. In describing the result of a vote, Robert’s prefers the terms “adopted” and “lost.” Other parliamentary authorities use slightly different wording. The language of the Amend card above is based on Cannon’s Concise Guide to Rules of Order. Presiding officers often appreciate the simplicity and uniformity of “is adopted” and “is not adopted” over the more antiquated “lost.”

For some clients or more complicated motions, I prepare full page scripts for the specific motion. Other parliamentarians prefer complete scripts for the meeting. As noted by Nancy Sylvester in The Guerilla Guide to Robert’s Rules, a script gives the chair “not only the correct words to say but the confidence to say them.” Motions, reports of committees, and even entire conventions can be scripted.

KEEPING TRACK OF THE PARLIAMENTARY SITUATION

In larger assemblies and conventions, it is particularly important for the parliamentarian to keep track of motions made and who has spoken. Such information can assist the chair in assigning the floor (since debate should alternate and no one should speak more than twice to the same motion), and it can be a lifesaver in the event of a motion to Reconsider (both for determining who spoke earlier as well whether the motion to Reconsider is timely in a multiday convention). Although formats vary, many parliamentarians keep a “Parliamentarian’s Log,” which summarizes each motion made, whether it was seconded, who debated on each side of the motion, as well as any secondary motions, and whether each motion was adopted or rejected.

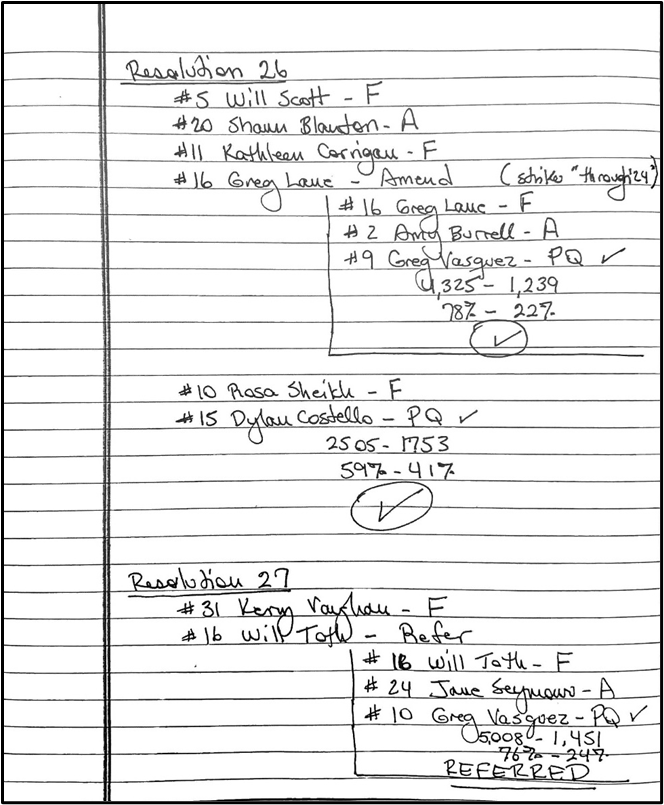

A Parliamentarian’s Log should be what works best for a specific parliamentarian. (See Notes and Comments on Robert’s Rules, Fifth Edition, p. 187-188) I like to track the motion, speakers and mics (as well as which side they spoke on), the wording of motions, and the outcome of votes. Here is a page from the Parliamentarian’s Log. NOTE: “F” means “FOR.” “A” means “Against.” “PQ” is for “Previous Question.” Subsidiary motions get separated to the right, so as to not get mixed with the main motion.

The Parliamentarian’s Log has more uses than one might think. At times, a presiding officer will ask about debate, in order to see the number of speakers and how many on each side. On other occasions, after debate on various motions, a member has suggested there has been no debate on the main motion. Imagine the assembly’s reaction when the presiding officer immediately calls out the name of every speaker and microphone on the proposal!

CONCLUSION

Parliamentarians need to find their own style. While not all of these methods will work for every meeting, parliamentarians who know additional techniques for recognition, voting, assisting the chair, and tracking the parliamentary situation will better serve their clients and find themselves in greater demand.

Jim Slaughter has been a Certified Professional Parliamentarian-Teacher for over 30 years. In addition, he is an attorney, Professional Registered Parliamentarian, and past President of the American College of Parliamentary Lawyers. He is the author of four books on meeting procedure, including two books updated for the new Robert’s 12th Edition—Robert’s Rules of Order Fast Track and Notes and Comments on Robert’s Rules, Fifth Edition. Jim has served as parliamentarian for many of the largest associations in the country and was recently recognized by Lawyers Weekly in its first class of eleven “NC Legal Icons.” Numerous parliamentary charts, articles, and resources can be found at www.jimslaughter.com.

© American Institute of Parliamentarians. Parliamentary Journal, August 2023. Reprinted with permission.