Freezing and Reducing your Taxable Estate with Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts (GRATs)

Likely the most effective and popular advanced planning techniques are the use of a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (“GRAT”) or an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (“IDGT”). The general idea of both techniques is to transfer assets expected to appreciate in an amount that exceeds the current month’s Applicable Federal Rate or Section 7520 (120% of the AFR) rate and pass the excess growth to non-charitable beneficiaries, all while using little or none of the individual’s basic exclusion. In this part, I will discuss GRATs, which are likely the most sophisticated advanced planning too; used by estate planners.

GRATs

A Grantor Retained Annuity Trust or “GRAT” is an irrevocable grantor trust that an individual transfers assets to in return for the right to receive annuity payments from the trust over a specified term of years. One of the primary mechanisms which makes this tool so powerful is the “grantor trust” status of the instrument. Although the trust is irrevocable, it maintains grantor trust status which means it is still owned by the grantor (i.e. the individual transferring the assets) for income tax purposes and so the grantor is responsible for paying income tax on the appreciation during the term of the trust without making a gift and which can, therefore, further reduce the grantor’s taxable estate. Additionally, any transactions between the grantor and the GRAT are disregarded for capital gains tax purposes.

The term of the GRAT will generally be short, no more than 5 years, because if the individual dies during the term of the GRAT all the assets within the GRAT will be included in their taxable estate and, therefore, the GRAT will have provided little to no benefit.

If the individual survives the GRAT term, the appreciation of the assets which exceeds the Section 7520 rate for the month of the transfer will pass to the individual’s beneficiaries with little to no gift tax consequence if structured properly. The Section 7520 “hurdle rate” is an assumed interest rate equal to 120% of the AFR updated monthly by the IRS; however, typically the Section 7520 rate is lower than the expected appreciation of marketable assets. The lower the Section 7520 rate and the higher the actual appreciation of the assets within the GRAT, the more effective the tool will be.

Basic GRATs

Other than the length of the term of the GRAT, the annuity payments to be returned to the grantor is the biggest structuring decision. The annuity payments can be fixed or increase over time. Gift tax may be assessed at the beginning of the GRAT depending on how the GRAT is structured. The gift is assessed based on the present value of the remainder interest of the transferred assets at the assumed Section 7520 rate. Stated differently, the gift is the fair market value transferred to the trust less the present value of the annuity payments to be returned to the grantor. For example, if 12 million is transferred to a 2-year GRAT when the Section 7520 rate is 4.8%, with annual annuity payments of $6 million to the grantor, it is assumed that $891,648 will be transferred to the beneficiaries at the end of the term and gift tax would be assessed at a slightly lower amount. The amount subject to gift tax is less than the actual transfer of assets to the beneficiaries because the gift to a GRAT is based on the present value at the beginning of the GRAT term. Therefore, even if the GRAT is not structured in a manner to avoid gift tax, it still allows for a discounted gift at present value because the gift is calculated at the beginning of the GRAT term based on the Section 7520 rate. Using the same example as above, if the assets grew at 8% over the term of the GRAT, $1,516,800 would be passed to the beneficiaries while less than $891,648 would be subject to gift tax or as a credit towards one’s basic exclusion.

As you can see, when structuring a GRAT in the manner illustrated above there can be significant upside in making a discounted gift, especially when the appreciation exceeds the Section 7520 rate. However, the grantor uses all or a portion of their basic exclusion. For an individual who wishes to preserve their basic exclusion, this structure is not ideal. Additionally, for an individual who has used their basic exclusion or is making a transfer to a GRAT where the present value gift is more than their available basic exclusion, gift taxes may be due immediately when assets are transferred to the GRAT and so it does not meet the goal of passing assets to the beneficiaries free of gift tax consequences.

Eliminating Gift Tax Consequences with Walton GRATs

To minimize the potential for gift taxes, most practitioners use a zeroed-out or “Walton” GRAT. With a zeroed-out GRAT, the annuity payments are set up to where their present value is roughly equal to the assumed future value of the remainder interest given the Section 7520 rate and, therefore, either a $0.00 or nominal gift is made by the grantor. For example, in the case of a Section 7520 rate of 4.8%, $12,000,000 could be transferred to a 2-year GRAT and, instead of the grantor receiving a total of $12,000,000 in annuity payments, the grantor would receive two payments of $6,435,375, for a total of $12,870,750. Under the theoretical IRS assumed Section 7520 rate of 4.8%, all of the assets in the trust should be returned to the grantor. Accordingly, since the present value of the annuity payments is equal to the future value of the transferred assets at the Section 7520 rate, there is no gift in the eyes of the IRS. The grantor has zeroed out the GRAT and even if the GRAT performs at or below the Section 7520 rate, the assets are returned to Grantor and the only loss is the administrative cost of establishing it. However, if the assets in the aforementioned zeroed out GRAT grow at 8%, $611,220 will pass to the beneficiaries without any gift tax consequences or use of the basic exclusion. Essentially, the grantor and beneficiaries split the growth. The grantor gets back all growth equal to the assumed Section 7520 rate through the annuity payments and the remaining amount, or excess, goes to the beneficiaries.

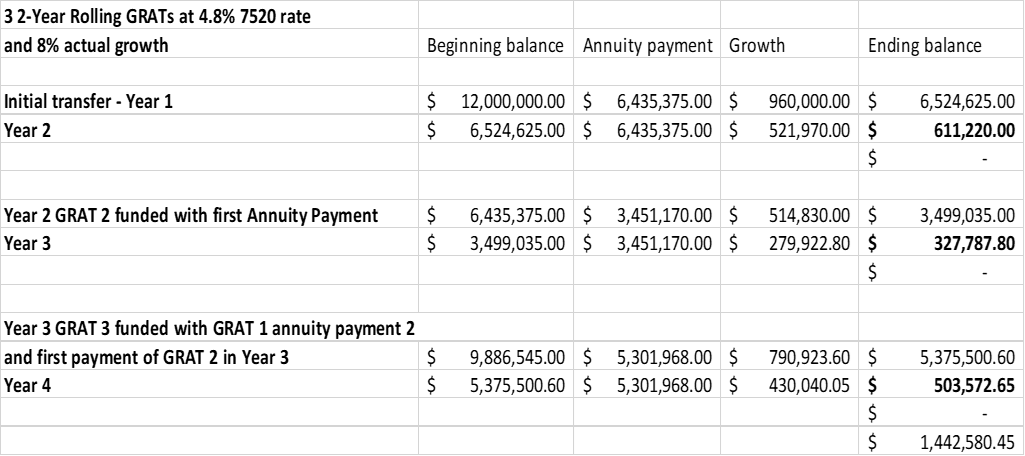

Maximizing Growth and Minimizing Risks with Rolling GRATs

While a short-term zeroed-out GRAT limits the risks associated with the GRAT i.e. dying before the terms ends and thus the assets being included in the grantor’s taxable estate as well as gift tax consequences, as you can see in the example above, a relatively low amount passes to the beneficiaries. To really leverage the zeroed-out GRAT, most practitioners use rolling GRATs. For example, three two-year GRATs, where the annual distribution funds the GRAT for the successive year. Assuming a constant Section 7520 rate of 4.8% and actual return of 8%, the grantor could roll three two-year GRATs, with the third GRAT ending in year four. If we begin with $12,000,000 and payments of $6,435,375, a total of $1,442,580 will be distributed to the beneficiaries if the grantor survives the three GRATs. However, if the grantor dies in year 3, the first GRAT was complete at the end of year two and, therefore, $611,220 has already been removed from the grantor’s estate. Conversely, using a four-year nearly zeroed-out GRAT ($3.41), only $1,147,331 would pass to the beneficiaries at the end of the term and if the grantor died in year three, nothing would pass to the beneficiaries and would instead be included in grantor’s taxable estate. With rolling GRATs, not only can the grantor increase the amount passing to the beneficiaries by compounding the appreciation using the annuity payments to fund the next GRAT, but the grantor also minimizes the risk of death during the GRAT term. See illustration below.

| 4 Year Zeroed-Out GRAT at 4.8% 7520 rate and 8% actual growth | |||

| Beginning balance | Annuity payment | Growth | Ending balance |

| $ 12,000,000.00 | $ 3,368,433.00 | $ 960,000.00 | $ 9,591,567.00 |

| $ 9,591,567.00 | $ 3,368,433.00 | $ 767,325.36 | $ 6,990,459.36 |

| $ 6,990,459.36 | $ 3,368,433.00 | $ 559,236.75 | $ 4,181,263.11 |

| $ 4,181,263.11 | $ 3,368,433.00 | $ 334,501.05 | $ 1,147,331.16 |

To learn more about estate tax planning, contact our office.